Aaron Bergman has written up a review of my book and posted it over at the String Coffee Table. It’s quite sensible and makes reasonable points, so I’m very glad he wrote it. Here are a few comments of my own about the points raised in the review. I don’t have time to discuss everything in it right now, but if someone feels that I’m not addressing an important point of Aaron’s let me know.

It’s true that the book isn’t “even-handed” in the sense of repeating many of the arguments made for string theory. One reason for this is that I assumed that essentially all my readers would have read at least something like one of Brian Greene’s books. I originally intended my book as something that would be published by a university press and be aimed at people with some background in the subject. The fact that it ended up being published by a trade publisher wasn’t my first choice, and the wide attention it is getting from people who know little about physics is a surprise to me, something I wasn’t counting on.

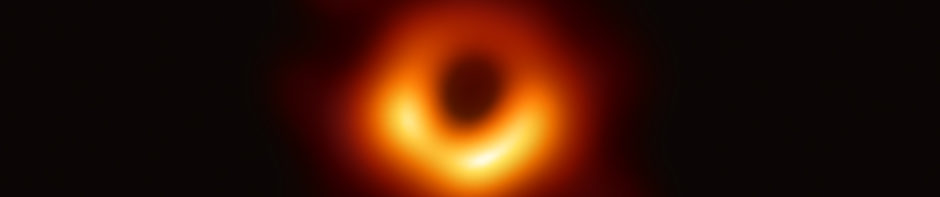

Instead of repeating many of the what seem to me highly over-hyped claims made for string theory and spending a lot of time explaining exactly how and why they’re over-hyped, I decided to just write down as accurately as possible how I see things. The black hole entropy calculations are an example of what I mean. I do mention these, but I think Aaron’s description of them as a “holy grail” vastly overestimates their signficance. It’s also true that string theorists still have not been able to do calculations for the case of physical 4-dimensional black holes. A truly honest description of the situation would require a detailed examination of exactly what has been calculated, and what remains still not understood. This is a highly technical business, not easy to extract from the often hype-filled literature, and I just didn’t think that even if I put the effort into doing this well, it would work as part of the book. Similar comments apply to the AdS/CFT story, where sorting through the hype and clearly distinguishing exactly what has been achieved and what hasn’t would be even more difficult.

People can compare what I have to say to what string theorists have to say, and see that there’s a different point of view on many things. If they have some expertise, they can look into these more deeply and decide for themselves. Aaron describes the book as “tendentious”, but I think it’s much more scrupulously accurate in its descriptions, honest and even-handed than any of the many books promoting string theory, essentially all of which contain vast amounts of misleading hype designed to give the reader an inaccurately optimistic view of the theory.

About the CC and supersymmetry: I re-read that section after Lubos’s review complained about it, and it was not clearly written. But the argument that I’m not giving SUSY credit for being wrong by 1060 instead of 10120 doesn’t make sense to me. Both are obviously in the same category of being completely off-base in a very fundamental way. The situation with SUSY is actually worse than non-SUSY, because in a non-SUSY theory the vacuum energy is not something that you can calculate even in principle. In a SUSY theory (before you turn on gravity), it’s the order parameter for supersymmetry-breaking, so has to have a scale of at least 100s of GeV to explain the lack of superpartners. Your theory of quantum gravity is supposed to ultimately explain the CC, and, for doing this, supersymmetry not only doesn’t improve the situation, it introduces a huge new problem you have to find some way around.

About the section on mathematics, and that I’m being petty about denying credit to string theory. Again, I think what I write is far more honest that just about anything string theorists have to say about the relation of string theory and mathematics, much of which is based on alotting to string theory purely QFT results.

About S-matrix theory, Chew, Capra. I think the lesson of what happened with S-matrix theory is an incredibly important one, and suspect that someday history will repeat itself. Before asymptotically free theories, people were convinced they had a good argument that QFT couldn’t be fundamental, just as many people are now convinced that problems with quantizing gravity imply that QFT can’t be fundamental. The arguments from Chew and Capra about getting rid of symmetry arguments and QFT in favor of the bootstrap are all too similar to things one hears these days from some string theorists. As for the denial of reality by Chew and Capra, post-QCD, there is no analog yet in the case of string theory. But, if someone finds a better way of quantizing gravity and getting unification, I’m willing to bet that, just like in the case of S-matrix theory, most theorists will move on, but some will refuse to ever give up on string theory and deny reality. We’ll see what happens. Eastern religions are a lot less popular in the US these days than they were in the 70s, so I don’t think there will be a new “The Tao of Physics”. But, already, if you take a look at Susskind’s “The Cosmic Landscape”, it holds up as science no better that Capra’s book.

About describing string theory as a cult with Witten as its guru. I believe Joao Magueijo in his book explicitly does this, and I can think immediately of three well-respected physicists or mathematicians who have, unprompted, used this description in conversations with me. Based on my experience, I’m pretty sure that if you sample non-string theorist physicists, you’re going to find many people who would describe the behavior of string theorists as “cult-like”. This behavior is described by Lee Smolin as “groupthink” and he has a lot to say about it. I wrote that I don’t think it’s useful to describe string theory as a religious cult, because the phenomena are significantly different, but I would characterize the behavior of some string theorists in recent years as “cult-like”. Some people exhibit a disconnect from the reality of the problems of the theory that is much like the way members of a cult behave in face of evidence contrary to their beliefs. Lubos is an extreme case, but there’s lots of others, of varying degrees. Describing Witten as the field’s “guru” I think is actually uncontroversial. There’s nothing wrong with having “gurus”, as long as you realize they are sometimes wrong. People who have demonstrated great amounts of knowledge and wisdom deserve to be listened to very seriously, but no one is ever right about everything.

About the Bogdanovs. The main reason I wrote about the Bogdanov story, (besides for its entertainment value), is that I think it shows conclusively that in quantum gravity in general, many people have lost the ability or willingness to recognize non-sense for what it is. Sure, this is not specifically a string theory problem, but it’s also not a problem specific to non-string theorists doing quantum gravity. This was swept under the rug at the time, and attributed to a few lazy referees, rather than dealt with as a serious problem that needs to be addressed if the field is not going to drown under an increasing tide of crap, and I think this was a big mistake, with the tide rising since then. I don’t apologize at all for writing about it in the book. As for the inclusion of the e-mail describing the reaction of the string group at Harvard, I don’t know its author, but I was assured by its recipient that it was legitimately from someone who was visiting there at the time. One member of the string theory group at Harvard is Lubos, and he has repeatedly defended the work of the Bogdanovs on his blog as legitimate science, no worse than much else of what is published in this field.

About Hagelin. Again, I wrote about him in the context of a chapter examining the difficulties involved in deciding what is science and what isn’t. More specifically, how do you tell who’s a crackpot and who isn’t? There are plenty of people out there whose ideas about physics are uniformly incoherent and easy to dismiss, but there are also cases like Hagelin, who combines excellent research credentials with crackpot ideas about science. How do you decide who is a crackpot and who isn’t? What about Lubos, what about Susskind? Many string theorists seem to hold the opinion that I’m one. Lacking the normal sort of discipline that comes from confrontation with experiment, a scientific field is in a very tricky state, and needs to be careful to enforce high standards of what makes sense and what doesn’t, and not let pseudo-science take over. Aaron notes that most of the audience at the Toronto panel discussion voted against the anthropic landscape, but he doesn’t mention that anthropism seemed to be a majority opinion amont the panelists, who are the ones who hold power. This is an extremely dangerous situation for this field. I don’t think the possibility that some readers of my book are going to get the impression that most string theorists are not doing science is anywhere near as much of a problem as the fact that quite a few powerful ones definitely aren’t anymore.

About comments on this blog. Please avoid adding to the noise level by posting non-substantive or off-topic comments, engaging in repetitive arguments that go nowhere, promoting your own ideas that have nothing to do with the posting, or generally making comments that have nothing new to say that hasn’t been said many times here already.