If I’m going to point to something about string theory and say the same things as always about it, seems best to first start with the opposite, an item about something really worth reading.

- This spring I’ve been teaching a graduate course aimed at getting to an explanation of the Standard Model aimed at mathematicians. The first few weeks have been about quantization and quantum mechanics, today I’m starting on quantum field theory, starting with developing the framework of non-relativistic QFT. While trying to figure out how best to pass from QM to QFT, I’ve kept coming across various aspects of this that I’ve always found confusing, never seen a good explanation of. Today I ran across a wonderful article by Thanu Padmanabhan, who I knew about just because of his very good introductory book on QFT, Quantum Field Theory: The why, what and how. The article is called “Obtaining the Non-relativistic Quantum Mechanics from Quantum Field Theory: Issues, Folklores and Facts” and subtitled “What happens to the anti-particles when you take the non-relativistic limit of QFT?” It contains a lot of very clear discussion of issues that come up when you try and think about the QM/QFT relationship, a sort of thing I haven’t seen anywhere else.

Looking for more of Padmanabhan’s writings, I was sad to find out that he passed away in 2021 at a relatively young age, which is a great loss. For more about him, there’s a collection of essays by those who knew him available here.

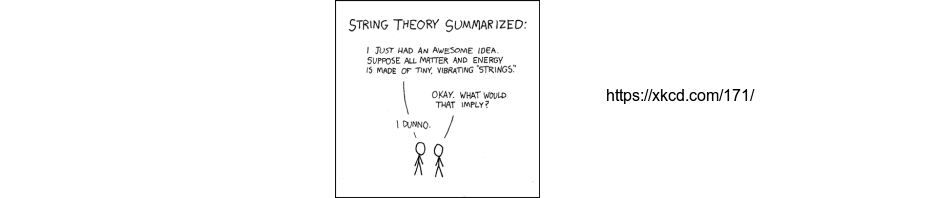

- For something I can’t recommend paying more attention to, New Scientist has an article labeled How to Test String Theory, which is mostly an interview with Joseph Conlon. Conlon’s goal is to make the case for string theory, in its original form as a unified theory with compactified extra dimensions. On the issue of testability there’s nothing new, just the usual unfalsifiable story that among all of the extra stuff (moduli fields, axions, extra dimension, extended structures) that appears in string theory and that string theorists have to go to great trouble to make non-observable, it’s in principle conceivable that somebody might observe one of these things someday. But, that’s not really what people mean when they ask for a test. For details of the sort of thing he’s talking about in the New Scientist article, see here.

I strongly disagree with Conlon about some of what he’s saying, but the situation is very much like it has always been with many string theorists since way back to nearly forty years ago. We don’t disagree about the facts, it’s just that I’ve always looked at these facts and interpreted them as showing string theory unification ideas to be unpromising, whereas string theorists like Conlon somehow find reasons for optimism, or at least for believing there’s no better thing to do with their time. Last time I was in Oxford, Conlon invited me to lunch at his College and I enjoyed our conversation. I think we agreed on many topics, even about what is going on in string theory, but it looks like we’re always going to have diametrically opposed views on this particular question. For more from him, as far as popular books by string theorists go, his Why String Theory? book is about the best there is, see more about this here.

Update: A couple more.

- Curt Jaimungal has a conversation with Lee Smolin.

- Andy Strominger is giving talks on Celestial Holography at the KITP “What is String Theory?” program, first one is here. Lots of questions from the audience. One thing he makes clear is that this is not leading to a theory of quantum gravity. Stringking is back, his comments on this:

KITP program on what is string theory such a joke this week. Strominger shilling his celestial vaporware.

I was in high school, just learning calculus, and T. Padmanabhan was doing his Master’s at University College in Thiruvanantapuram, and one summer he organized with a co-student or two, an after hours class for interested students, where he taught the Calculus of Variations, Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics and made it all intelligible to me – an amazing teacher!

I wish that I had kept contact; but that one summer is a memory I cherish.

I realized it’s Padmanabhan who’s written the mesmerizing textbook “Sleeping Beauties in Theoretical Physics”… such a loss…

A lot of this seems to be an embedding of “personal Bayesianism” into the scientific project. So people start with different personal “creedences” of some idea (perhaps highly correlated to their involvement in it) and update more or less frequently with new evidence according to their personal estimate of the value of the evidence, conditional probabilities, etc. So it’s not really surprising to see different estimates of say [10%, 90%] creedences on theories based on some empirical “my truth” basis like this. Especially in some cases where there is no real evidence to update on, or priors to estimate.

What seems a bit different here is the idea of “expected future personal Bayesianism”, meaning personal forecasts of future progress getting rolled into current credeences with very high probability. If the progress was that automatic it would already have happened. So very high “expected future personal Bayesianism” creedences based on very little evidence or substance seem to be the cause of the sociological argument here.

Sean Carroll’s long podcast on the state of Physics kind of outlines the case for this, but while the first half of the podcast is very good, when he veers into the defence of “expected future personal Bayesianism” and insider hiring practices in academia it is less impressive, although I think very honest. Believing in the serial correlation of past individual scientist’s successes with future successs over very long time horizons is counter to quite a bit of evidence.

The question is what is the proposed alternative to insider “expected future personal Bayesiansm?” I suspect it would look something like the rich guy funding models of Perimeter and Simons, run like a venture capital fund, with the expected return of each investment near zero, but high overall (societal) returns to a diversified enough portfolio of ideas and individuals. But more funding to entrenched incumbents supported by “look these guys are really smart, and they almost did something incredibly cool 20 years ago” probably has a very average rate of return, especially if the pitch-deck (in the form of popular science books) is a bit cooked.

An even bigger problem is whether these theories of Planck-scale physics make sense to attempt, given they can’t be directly proven or evaluated. But although I see no evidence of this, my “expected future personal Bayesianism” gives me hope that they can.

Joseph Conlon is a very nice guy with a passion for both the mathematics and physics(?) found in String Theory. However, in the New Scientist interview his role as a defendant for the continuing relevance of String Theory (rather than a degenerate research program) falls pretty flat – he comes over more as a ‘Witness for the Prosecution’.

Thanks, Peter. I also enjoyed our lunch in Oxford. No personal quarrel; but I am as mystified by your views as you seem to be about mine.

If one (a) accepts that there is an awful lot we don’t know about our current universe and (b) think that research on these questions is worthwhile (and my impression is we agree on both points) then I cannot really understand the hostility to string theory as a subject, especially when compared to the alternatives, although I could understand some allergic reaction to some of the bad PR done in the name of string theory.

Likewise, I can’t really grok why you seem hostile to ideas if they have the label `string theory’ attached, but indifferent if the same ideas appear without that label. For example, the physics part of the interview concerns ideas for physics in the epoch between inflation and BBN (e.g. moduli domination), which you seem quite scathing about above.

We really know essentially nothing, observationally, about this epoch. Nil, zip, dada. And it could cover up to a factor of 10^30 in time. So surely all theorists in the particle theory / cosmology zone with at least some interest in pheno should care about ideas for what could be in this epoch and how we could test them? This is up to half the lifetime of the universe on a log scale! Of course we should think about what happened them and how we might observe them.

I don’t recall any posts by you criticising cosmologists who write papers about this era as unfalsifiable, etc — but many of the same/similar ideas (early matter domination/trackers/quintessence/kination etc) become ‘not even wrong’ when in a string context: and I cannot really understand why.

I can ‘get’ hostility to string theory as a subject from those who think that we should all work on climate physics, AI or quantum computing. I can get allergic reactions to bad PR. But I can’t really understand intellectual hostility from anyone with a broad-minded interest in particle theory.

Joe,

In this particular case the hostility is to claims that effects of moduli fields are a “test of string theory”, which is misleading (a more accurate description of the implications of such fields would be as serious evidence against string theory).

In general I don’t spend my time criticizing cosmologists or anyone else for working on whatever they find interesting, however unpromising or misguided it looks to me. The focus on string theory is because the way it has been pursued and hyped to the public and other scientists over the last 40 years has done a lot of damage to the kind of research I care about. This first drew almost all resources in the field to one speculative idea, which was bad enough. Now after decades of this idea not working out, it has discredited all research on unified theories.

I do try and spend my time on more positive pursuits, but the hype campaign won’t stop and actually just gets more disturbing (see the wormhole fiasco, or the recent Brian Greene panel). About the only other person criticizing this is Sabine Hossenfelder, and my point of view is very different than hers on the problem (no, it’s not “Lost in Math”).

Those aren’t my words though. In what I say, I try and be super-careful about any expression like ‘test of string theory’. As you know, if you talk to journalists (which generally scientists should do if asked) you don’t control the blurb and you don’t control the title: and likely something will be picked that you would never choose yourself.

So you either have to live with headlines you would rather were different, or not say anything at all: and I choose the former.

It looks like some chapters have been recalled in your latest qftmath notes version. I was wondering if Padmanabhan’s article had influenced your treatment.

Art,

I’ve just this afternoon uploaded the latest version of the notes, see

https://www.math.columbia.edu/~woit/QFT/qftmath.pdf

The material I’ve been lecturing on the last week or two and have now finished (chapter 7) has been about non-relativistic qft, which is generally considered too simple to make it into most QFT books, which start with the relativistic theory. But it seems to me best to first understand the non-relativistic theory, where anti-particles decouple, making the whole story much more straightforward.

The earlier version I had posted had a partial chapter 7, including something I’d started writing on propagators. When I started adding more and gave a lecture, I realized that I was doing things in a confused and overly complicated way. Normally I figure this out while preparing a lecture, this time I didn’t realize it until I was actually in the middle of the lecture (and realized that an argument had gone in a circle and come back to essentially the same starting point…). Apologies to the students for putting them through that, but others I hope will benefit because the experience made it possible to write up much clearer notes.

So, no, Padmanbhan not responsible, but preparing and delivering a lecture was, as always in teaching, very educational for me.

Got it, thanks. I’m looking forward to the reappearance of Chapters 9 and 10 in a future version.

Art,

Forgot to include those in this latest version. Will be getting to that part of the course later in the week and be rewriting them, new version should appear in a week or two.

Peter, you have previously commented on exciting-sounding analogies between bench-top experiments and black holes, including the information-loss paradox. Yet Nature Reviews Physics is again highlighting these analogies as sources of profound insights; see https://www.nature.com/articles/s42254-023-00630-y.epdf?sharing_token=zj4iqWa8yEwZ-i4Fl6fAitRgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0Nz0uC7Et1O9sYRTMTUg9QS9YGeXjxcQPTc-Ho86x7uS-7F0WJfvtsbRyG4MuSBzadIgdFFCqIuydBu_jceodTM88QhNAtDbDJSby0DN9GCTpPIuYpnXNwxYECfp0qBwBg%3D. Is this work significant because new insights are obtained into otherwise intractable systems, or is it because the analogies simply sound cool? Sorry for what may be naive questions.

Michael Weiss,

This sort of thing has never made any sense to me. There’s something obviously absurd on its face about claiming “I’m going to study motion of a fluid in a lab, and learn about quantized space-time degrees of freedom.” I don’t see how it’s any different than me saying “I’m going to test my quantum gravity theory in which some variable satisfies a quadratic equation with solution a parabola by going outside and throwing a ball whose trajectory should follow the same parabola.”

This Nature paper is somewhat less nonsensical than the Nature wormhole fiasco paper, and at least these authors didn’t hold a press conference and convince Quanta to make a video about it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pcd911qSTBk

Cosmological constants – Part 1 (Thanu Padmanabhan)

Oxford -Cambridge collaboration

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sPkspt1XrKQ

Cosmological constants – Part 2 (Thanu Padmanabhan)