In the 70s, Mumford discovered p-adic analogues of classical uniformizations of curves and abelian varieties, which generalized Tate's p-adic uniformization of elliptic curves. Besides its significance for moduli, Mumford's construction can be also viewed as a highly nontrivial example of rigid analytic geometry. We shall start by reviewing the classical Schottky uniformization of compact Riemann surfaces and then introduce the dictionary between Mumford curves and p-adic Schottky groups. With the aid of the Bruhat-Tits tree of  , we can illustrate examples of Mumford curves whose geometry and arithmetic are rich, and explain why the answer to life, the universe and everything should be changed.

, we can illustrate examples of Mumford curves whose geometry and arithmetic are rich, and explain why the answer to life, the universe and everything should be changed.

This is a note I prepared for my second Trivial Notions talk at Harvard, Fall 2012. Our main sources are [1], [2] and [3]. Some pictures are taken from [4], [1], and [5].

Tate curves

Tate curves

A well-known example of complex uniformization is the uniformization of any elliptic curve  by the complex plane

by the complex plane  . Namely, we have a complex-analytic isomorphism

. Namely, we have a complex-analytic isomorphism  for some lattice

for some lattice  and

and  . The general scheme of uniformization is to find a certain universal (usually analytic) object and realize algebraic curves and varieties as the quotient of this universal object by a group action. This can yield results immediately: in the example of elliptic curves, we easily know that the

. The general scheme of uniformization is to find a certain universal (usually analytic) object and realize algebraic curves and varieties as the quotient of this universal object by a group action. This can yield results immediately: in the example of elliptic curves, we easily know that the  -torsion group

-torsion group ![$E[n]\cong (\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z})^2$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_263624084_-5.gif) , which is not entirely obvious in the purely algebraic setting.

, which is not entirely obvious in the purely algebraic setting.

The idea of finding a  -adic analogue of the uniformization of elliptic curves goes back to Tate. Replacing

-adic analogue of the uniformization of elliptic curves goes back to Tate. Replacing  and

and  by

by  and

and  , we can ask the following naive question: for an elliptic curve

, we can ask the following naive question: for an elliptic curve  , does there exist a

, does there exist a  -lattice

-lattice  such that

such that  This question does not quite make sense: the

This question does not quite make sense: the  -span of any element

-span of any element  is not discrete since

is not discrete since  when

when  under the

under the  -adic absolute value. However, the multiplicative group

-adic absolute value. However, the multiplicative group  has lots of

has lots of  -lattices:

-lattices:  for any

for any  . So we may seek a

. So we may seek a  -adic analogue of

-adic analogue of ![$$\xymatrix{\mathbb{C}^\times/q^\mathbb{Z}\ar[rr]^\cong & &E(\mathbb{C}),\\ & \mathbb{C}/\Lambda_\tau \ar[lu]^{\exp(2\pi i\cdot)} \ar[ru]^\cong& }$$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_103923183_.gif) where

where  (

( since

since  ).

).

Recall that the isomorphism  is given by

is given by  and

and  is defined by the equation

is defined by the equation  Since

Since  and

and  are translation invariant, we can write them as a Fourier series

are translation invariant, we can write them as a Fourier series  in terms of

in terms of  . After an explicit change of coordinates to get rid of factors of

. After an explicit change of coordinates to get rid of factors of  and denominators, we obtain the equation

and denominators, we obtain the equation  where

where ![$a_4(q), a_6(q)\in q \mathbb{Z}[{[}q]]$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_105421891_-5.gif) , together with the universal power series

, together with the universal power series

which converge as long as

which converge as long as  . The miracle is that these power series make perfect sense over any field; in particular, they converge for

. The miracle is that these power series make perfect sense over any field; in particular, they converge for  ,

,  . In this way, Tate proved the following theorem.

. In this way, Tate proved the following theorem.

with

with  , there exists an elliptic curve

, there exists an elliptic curve  such that there is a Galois-equivariant "

such that there is a Galois-equivariant " -adic analytic" isomorphism

-adic analytic" isomorphism

Observe that  implies that

implies that  , hence reducing mod

, hence reducing mod  we obtain the equation

we obtain the equation  which defines a singular cubic curve with a node and tangent lines

which defines a singular cubic curve with a node and tangent lines  and

and  at

at  . In other words,

. In other words,  has split multiplicative reduction. Conversely, Tate also proved that any elliptic curve with split multiplicative reduction over

has split multiplicative reduction. Conversely, Tate also proved that any elliptic curve with split multiplicative reduction over  is isomorphic to a unique

is isomorphic to a unique  with

with  ,

,  . These elliptic curves are called Tate curves, best viewed as elliptic curves over

. These elliptic curves are called Tate curves, best viewed as elliptic curves over ![$\Spec \mathbb{Z}[{[}q]]$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_203576354_-5.gif) . As an immediate consequence of the

. As an immediate consequence of the  -adic uniformization, one can easily compute the Galois action on the Tate modules of Tate curves.

-adic uniformization, one can easily compute the Galois action on the Tate modules of Tate curves.

Schottky uniformization

Schottky uniformization

Now the natural question becomes: can we construct the  -adic uniformization for smooth projective curves of genus

-adic uniformization for smooth projective curves of genus  ? One may think of Koebe's uniformization of compact Riemann surfaces as the quotient of the upper half plane

? One may think of Koebe's uniformization of compact Riemann surfaces as the quotient of the upper half plane  by Fuchsian groups

by Fuchsian groups  . Unfortunately, since the

. Unfortunately, since the  -adic topology is totally disconnected, the notion of "simply-connected" in the

-adic topology is totally disconnected, the notion of "simply-connected" in the  -adic world is more subtle than in the complex world (e.g., all curves with good reduction are "simply-connected", if defined properly). It turns out that the right analogue Mumford discovered is the Schottky uniformization.

-adic world is more subtle than in the complex world (e.g., all curves with good reduction are "simply-connected", if defined properly). It turns out that the right analogue Mumford discovered is the Schottky uniformization.

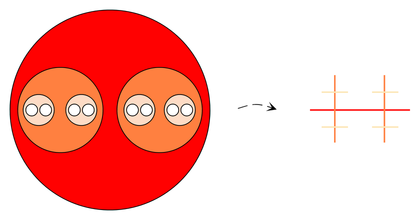

,

,  and

and  in the complex plane with disjoint interiors, the two Mobius transformations

in the complex plane with disjoint interiors, the two Mobius transformations  sending the exterior of

sending the exterior of  to the interior of

to the interior of  generate a discrete subgroup

generate a discrete subgroup  of

of  (i.e., a Kleinian group).

(i.e., a Kleinian group).  is a free group of rank 2 and its limit set

is a free group of rank 2 and its limit set  consists of the dust left out by iterations of

consists of the dust left out by iterations of  on the common exterior of the 4 circles. It is easy to see that a fundamental domain of

on the common exterior of the 4 circles. It is easy to see that a fundamental domain of  acting on

acting on  can be chosen as the common exterior of the 4 circles with two pairs of circle boundaries identified. In this way

can be chosen as the common exterior of the 4 circles with two pairs of circle boundaries identified. In this way  becomes a compact Riemann surface of genus 2.

becomes a compact Riemann surface of genus 2.

In general, a Schottky group of rank  is a free group constructed as above using

is a free group constructed as above using  pairs of Jordan curves. For a Schottky group

pairs of Jordan curves. For a Schottky group  of rank

of rank  ,

,  is a compact Riemann surface of genus

is a compact Riemann surface of genus  . Conversely, any compact Riemann surface can be obtained from some Schottky group. Motivated by this, we define

. Conversely, any compact Riemann surface can be obtained from some Schottky group. Motivated by this, we define

Analogously, for a  -adic Schottky group, we denote by

-adic Schottky group, we denote by  the set of limit points and

the set of limit points and  . We now hope that the quotient

. We now hope that the quotient  admits a structure of an algebraic curve. Let us show an example to illustrate that the expectation is not completely ridiculous.

admits a structure of an algebraic curve. Let us show an example to illustrate that the expectation is not completely ridiculous.

be the free group of rank 1 generated by

be the free group of rank 1 generated by  . Then

. Then  is discrete, thus is a

is discrete, thus is a  -adic Schottky group. The limit set

-adic Schottky group. The limit set  is exactly

is exactly  . So

. So  is a Tate curve, which has genus 1 and split multiplicative reduction as we have already seen.

is a Tate curve, which has genus 1 and split multiplicative reduction as we have already seen.

In general, Mumford proved the following influential theorem.

is a

is a  -adic Schottky group of rank

-adic Schottky group of rank  . Then there is a

. Then there is a  -adic analytic isomorphism

-adic analytic isomorphism  , where

, where  is smooth projective curve of genus

is smooth projective curve of genus  over

over  . Such a curve

. Such a curve  is called a Mumford curve.

is called a Mumford curve.

Mumford curves and Trees

Mumford curves and Trees

You may wonder whether an arbitrary smooth projective curve of genus  admits such a

admits such a  -adic uniformization. But you are smart enough to figure out the answer at once: no, otherwise it would be meaningless to invent the terminology "Mumford curve". At least, as we already know, the elliptic curves which are Mumford curves should have a specific reduction type. This actually generalizes.

-adic uniformization. But you are smart enough to figure out the answer at once: no, otherwise it would be meaningless to invent the terminology "Mumford curve". At least, as we already know, the elliptic curves which are Mumford curves should have a specific reduction type. This actually generalizes.

is a

is a  -adic Schottky group of rank

-adic Schottky group of rank  . Then the Mumford curve

. Then the Mumford curve  has split degenerate stable reduction. Conversely, any smooth projective curve with split degenerate stable reduction is a Mumford curve.

has split degenerate stable reduction. Conversely, any smooth projective curve with split degenerate stable reduction is a Mumford curve.

Here stable means (as usual) that the reduction has at most ordinary double points (a.k.a. nodes) and any rational component (if any) meets other components at least 3 points; split degenerate means that the normalization of all components are rational and all nodes are  -rational with two

-rational with two  -rational branches.

-rational branches.

To see the reason why the theorem is plausible, we need to go a bit into Mumford's construction of  as a rigid analytic space. Remarkably, the analytic reduction of

as a rigid analytic space. Remarkably, the analytic reduction of  is closely related to the Bruhat-Tits tree of

is closely related to the Bruhat-Tits tree of  .

.

is a free

is a free  -module of rank two

-module of rank two  . Two lattices

. Two lattices  and

and  are said to be equivalent if

are said to be equivalent if  for some

for some  . For any two lattices

. For any two lattices  ,

,  , we can find a

, we can find a  -basis

-basis  of

of  such that

such that  is a

is a  -basis of

-basis of  (

( ), then the distance

), then the distance ![$d([\Lambda], [\Lambda'])=|a-b|$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_267241729_-5.gif) is well defined on lattice classes.

is well defined on lattice classes.

of

of  is a tree consisting of

is a tree consisting of

- vertices: lattice classes

![$[\Lambda]$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_43025386_-5.gif) .

. - edges:

![$[\Lambda]$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_43025386_-5.gif) and

and ![$[\Lambda']$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_98595232_-5.gif) are adjacent if and only if

are adjacent if and only if ![$d([\Lambda],[\Lambda'])=1$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_138093823_-5.gif) .

.

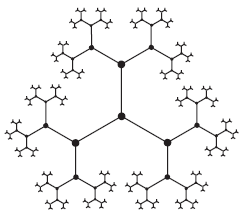

for

for  is shown in the following picture.

is shown in the following picture.

Notice that edges coming out of a vertex ![$[\Lambda]$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_43025386_-5.gif) correspond bijectively to lines in

correspond bijectively to lines in  , i.e., points in

, i.e., points in  , all vertices with given distance

, all vertices with given distance  to

to ![$[\Lambda]$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_43025386_-5.gif) correspond bijectively to

correspond bijectively to  and the infinite ends correspond bijectively to

and the infinite ends correspond bijectively to  .

.

The fact that  acts on the tree

acts on the tree  already helps us to retrieve the following theorem which is not obvious using purely group-theoretic methods. This replaces "free" by the weaker requirement "torsion-free", and consequently we can construct many

already helps us to retrieve the following theorem which is not obvious using purely group-theoretic methods. This replaces "free" by the weaker requirement "torsion-free", and consequently we can construct many  -adic Schottky groups arithmetically (e.g., groups coming from quaternionic orders).

-adic Schottky groups arithmetically (e.g., groups coming from quaternionic orders).

is a

is a  -adic Schottky group if and only if it is discrete, finitely generated and torsion-free.

-adic Schottky group if and only if it is discrete, finitely generated and torsion-free.

acting on a vertex of

acting on a vertex of  is conjugate to

is conjugate to  , a compact subgroup. Since

, a compact subgroup. Since  is discrete, we know this stabilizer must be a finite group. But

is discrete, we know this stabilizer must be a finite group. But  is torsion-free, so we know that the action on

is torsion-free, so we know that the action on  is actually free. It follows that

is actually free. It follows that  is the universal covering of the quotient

is the universal covering of the quotient  and

and  is the fundamental group of

is the fundamental group of  . There is a finite subgraph

. There is a finite subgraph  such that

such that  retracts to it, hence the fundamental group is a free group generated by the loops of

retracts to it, hence the fundamental group is a free group generated by the loops of  .

¡õ

.

¡õ

More importantly, the tree  helps us to understand the analytic reduction of

helps us to understand the analytic reduction of  . Since the topology on

. Since the topology on  is totally disconnected, the idea of rigid analytic geometry is to "rigidify" the topology using affinoids, i.e., complements of open disks. We will not discuss the notion of analytic reduction in detail (cf., [6]), but the following example may be instructive.

is totally disconnected, the idea of rigid analytic geometry is to "rigidify" the topology using affinoids, i.e., complements of open disks. We will not discuss the notion of analytic reduction in detail (cf., [6]), but the following example may be instructive.

. It corresponds to the affinoid algebra

. It corresponds to the affinoid algebra ![$\mathbb{C}_p\langle z\rangle= \{\sum a_n z^n\in \mathbb{C}_p[{[}z]], a_n\rightarrow 0\}$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_208383321_-5.gif) . The analytic reduction is simply

. The analytic reduction is simply ![$\Spec \overline{\mathbb{F}}_p[z]$](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_248934735_-5.gif) , an affine line. Now consider a covering of

, an affine line. Now consider a covering of  by two affinoids

by two affinoids  and

and  . They correspond to the affinoid algebras

. They correspond to the affinoid algebras  and

and  . So the analytic reduction of

. So the analytic reduction of  with respect to this covering becomes a projective line (in

with respect to this covering becomes a projective line (in  ) and an affine line (in

) and an affine line (in  ) crossing at a node. Geometrically, this can be viewed as a "blow-up" operation at a closed point in the special fiber. In general, there is a bijection between projective integral model of algebraic curves and analytic reductions associated to its pure affinoid coverings.

) crossing at a node. Geometrically, this can be viewed as a "blow-up" operation at a closed point in the special fiber. In general, there is a bijection between projective integral model of algebraic curves and analytic reductions associated to its pure affinoid coverings.

Now one can cover  using smaller and smaller affinoids around the rational points

using smaller and smaller affinoids around the rational points  . The analytic reduction of

. The analytic reduction of  then becomes a huge tree of

then becomes a huge tree of  s crossing at nodes, with dual graph being exactly

s crossing at nodes, with dual graph being exactly  .

.

At this stage Mumford's result may be a bit more transparent. For a  -adic Schottky group

-adic Schottky group  , we can construct the quotient of

, we can construct the quotient of  by gluing the affinoids under the action of

by gluing the affinoids under the action of  to form a rigid analytic quotient curve and then apply a GAGA-type theorem to algebraize it. In particular, the reduction

to form a rigid analytic quotient curve and then apply a GAGA-type theorem to algebraize it. In particular, the reduction  should coincide with the quotient of the reduction of

should coincide with the quotient of the reduction of  by

by  , in other words,

, in other words,  has split degenerate reduction with dual graph

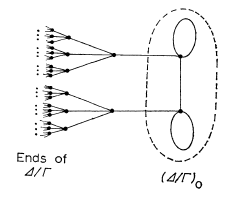

has split degenerate reduction with dual graph  ! We list the beautiful dictionary as by-products of Mumford's construction.

! We list the beautiful dictionary as by-products of Mumford's construction.

![\begin{center}

\begin{tabular}[h]{p{2.6cm}|p{5.7cm}}

dual graph of $\bar X$ & $(\Delta/\Gamma)_0$\\ \hline

$X(\mathbb{Q}_p)$ & ends of $\Delta/\Gamma$\\ \hline

$\bar X(\mathbb{F}_p)$ & edges coming from vertices of $(\Delta/\Gamma)_0$\\ \hline

Reduction map $X(\mathbb{Q}_p)\rightarrow \bar X(\mathbb{F}_p)$ & \centering $\{\text{ends of } \Delta/\Gamma\}\rightarrow \{\text{edges coming from vertices of } (\Delta/\Gamma)_0\}$

\end{tabular}

\end{center}](./latex/latex2png-MumfordCurves_45358586_.gif)

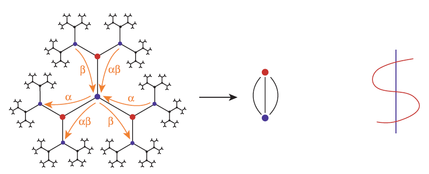

and

and  has action on the tree

has action on the tree  shown on the left (

shown on the left ( and

and  can be computed explicitly, cf., [4]). Then resulting quotient graph and reduction are shown on the right.

can be computed explicitly, cf., [4]). Then resulting quotient graph and reduction are shown on the right.

From Mumford's dictionary, we know that  is a hyperelliptic curve of genus

is a hyperelliptic curve of genus  with no

with no  -rational points and whose reduction is two rational curves crossing at three

-rational points and whose reduction is two rational curves crossing at three  -rational points (indeed, its equation can be written down explicitly using

-rational points (indeed, its equation can be written down explicitly using  -function). You can understand its "rich" geometry through staring at the dollar sign.

-function). You can understand its "rich" geometry through staring at the dollar sign.

To summarize, compared to the complex uniformization, Mumford's  -adic uniformization is weaker in the sense that not all curves can arise this way. But it may also be viewed as stronger in the sense that stronger results concerning its geometry and arithmetic may be achieved with the aid of the tree

-adic uniformization is weaker in the sense that not all curves can arise this way. But it may also be viewed as stronger in the sense that stronger results concerning its geometry and arithmetic may be achieved with the aid of the tree  (among others). Here is our final example due to Herrlich, which enormously improves the classical Hurwitz bound

(among others). Here is our final example due to Herrlich, which enormously improves the classical Hurwitz bound  for the number of automorphisms of curves of genus

for the number of automorphisms of curves of genus  over any field of characteristic 0.

over any field of characteristic 0.

Therefore you may want to change the answer to life, the universe and everything according to your favorite prime  .

.

References

[1]An analytic construction of degenerating curves over complete local rings, Compositio Math 24 (1972), no.2, 129--174.

[2]Schottky Groups and Mumford Curves (Lecture Notes in Mathematics), Springer, 1980.

[3]Non-archimedean uniformization and monodromy pairing, http://www.math.psu.edu/papikian/Research/RAU.pdf.

[4]The p-adic icosahedron, Notices of the AMS 52 (2005), no.7, 720--727.

[5]Indra's Pearls: The Vision of Felix Klein, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[6]Rigid Analytic Geometry and Its Applications (Progress in Mathematics), Birkhauser Boston, 2003.